September 2024, Great Documentary Photographers

September 2024, Great Documentary Photographers

Keeping you informed about happenings at Deliberate Light: photos to browse or buy, photography instruction (see also Digital Photo Academy), and services. Also, my thoughts on a photography subject: this month, Great Documentary Photographers. To get these newsletters by email a month before they are posted here, go to the DeliberateLight.com website and click on Newsletter Signup.

NEWS

Upcoming Workshops. I am scheduled to teach the following workshops on October 5 at Rittenhouse Square Park, Philadelphia. You can sign up here if interested.

· Mastering Your Camera Controls (1.5 hours) – DSLR/Mirrorless/Compact cameras (smartphone tutorial available separately)

· Composition in the Field (3 hours) – walking tour around the venue with instruction and hands-on practice composing photos (bring any camera)

New Photo.

Land Buoy. At the end of Washington Avenue in Philadelphia, jutting into the Delaware River is a hidden gem of a public park. Now known as Washington Avenue Green, the pier was originally the entry point for over a million immigrants to Philadelphia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Now a lovely green space, this spiral sculpture by Jody Pinto caps the end and is meant to be climbed, as my grandchild does, to view Philadelphia as it might have been seen for the first time from a ship coming in to dock. I have promised myself that I will climb it with them one day.

(Philadelphia, PA, 2024)

For a more detailed, enlarged view and to get it printed, see it on my website.

VIEWS

This month I am examining three historically important documentary photographers whose work I admire: Henri Cartier-Bresson, Dorothea Lange, and Gordon Parks. This newsletter is longer than I normally like, but I really admire these guys and they deserve the space.

What is documentary photography? It is the visual recording of significant scenarios, where “significant” can mean either historically significant or personally significant and “scenarios” can be people, places or things or any combination of them. Photojournalism often falls under this umbrella, as does street photography, as well as social justice photography. One characteristic of documentary photography that I appreciate is that it often conveys a story, small or large.

Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908 – 2004)

His first artistic training was as a painter, but then he discovered photography.

“I suddenly understood that a photograph could fix eternity in an instant.”

He was a co-founder of Magnum Photos, a photojournalism cooperative owned by its members that spawned some great photographers. Cartier-Bresson enunciated his approach to photography in his 1952 book “The Decisive Moment”, which is neatly summarized in a 1957 interview:

“There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. … Once you miss it, it is gone forever.”

Annie Leibovitz and Cindy Sherman and others who use highly staged scenarios, might feel left out, but I suspect that even they would agree that there is that moment sometime after all the staging when a photograph is best taken.

Few of Cartier-Bresson’s photos are technically perfect or artistically composed – he was more interested in capturing the essence of the moment than in creating beauty. The gift he gives the viewer is to let them make sense of the image he has captured, and, in that act, the viewer participates in making the story.

Behind the Gare St. Lazare, Paris, 1932.

His most often referenced photo, it is clear that Cartier-Bresson had to wait for this instant, probably recognizing the potential in the scene before the guy arrived in it.

Torcello, Near Venice, 1953.

The pointed bow of the gondola against the arch almost chasing the running woman make this marvelous scene. If he had waited a split second longer, this moment would have been “gone forever.”

Dorothea Lange (1895 – 1965)

Born in Hoboken and a life-long photographer, Lange’s professional career in photography did not really begin until 1918 in San Francisco doing mostly portraiture for about 15 years. Believing that “It is not enough to photograph the obviously picturesque,” she started photographing on the street which led to a job with the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a federal entity to protect farmers, to document the effect of the Great Depression. She was also asked by the government to take photographs in Japanese internment camps during WWII, but her photographs were deemed so controversial that they were impounded for the duration of the war.

Similar to Cartier-Bresson in her belief that “Photography takes an instant out of time, altering life by holding it still,” Lange managed to prove that documentary photographs can also be works of art. Her later work, though often still focused on social justice, turned more to beautifully composed fine art, resigning herself to the fact that her life-long social justice efforts had produced little concrete governmental action. Lange was a founder of the Aperture Foundation in 1952 (along with several others including Ansel Adams) to create a forum for fine art photography to advance creativity, inspire curiosity and encourage social justice.

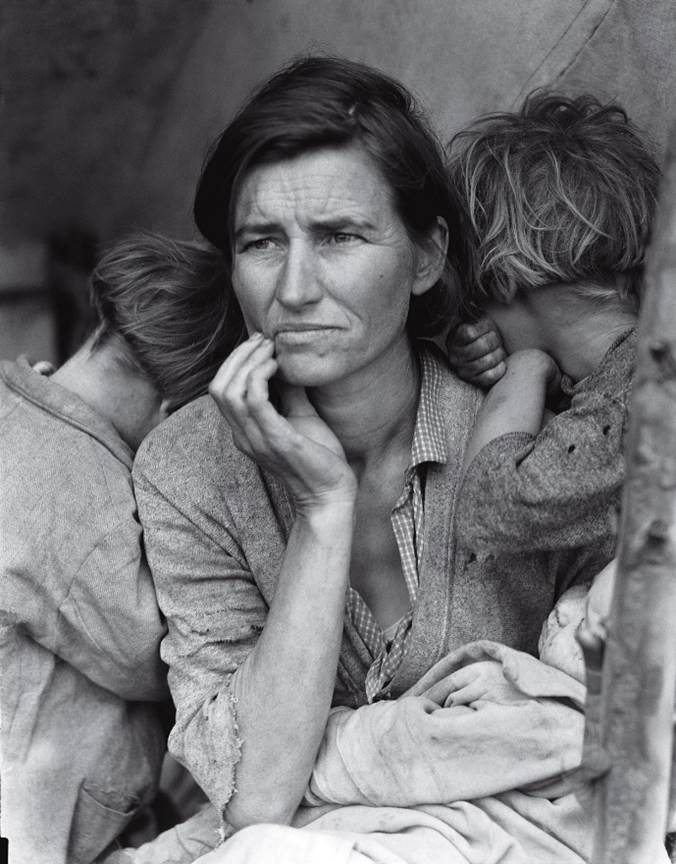

Migrant Mother, Nipoma, California, 1936.

This iconic Great Depression photo might be the most reproduced image ever. Lange’s extensive body of work for the FSA had the far-reaching effect of humanizing the dire consequences of the Depression.

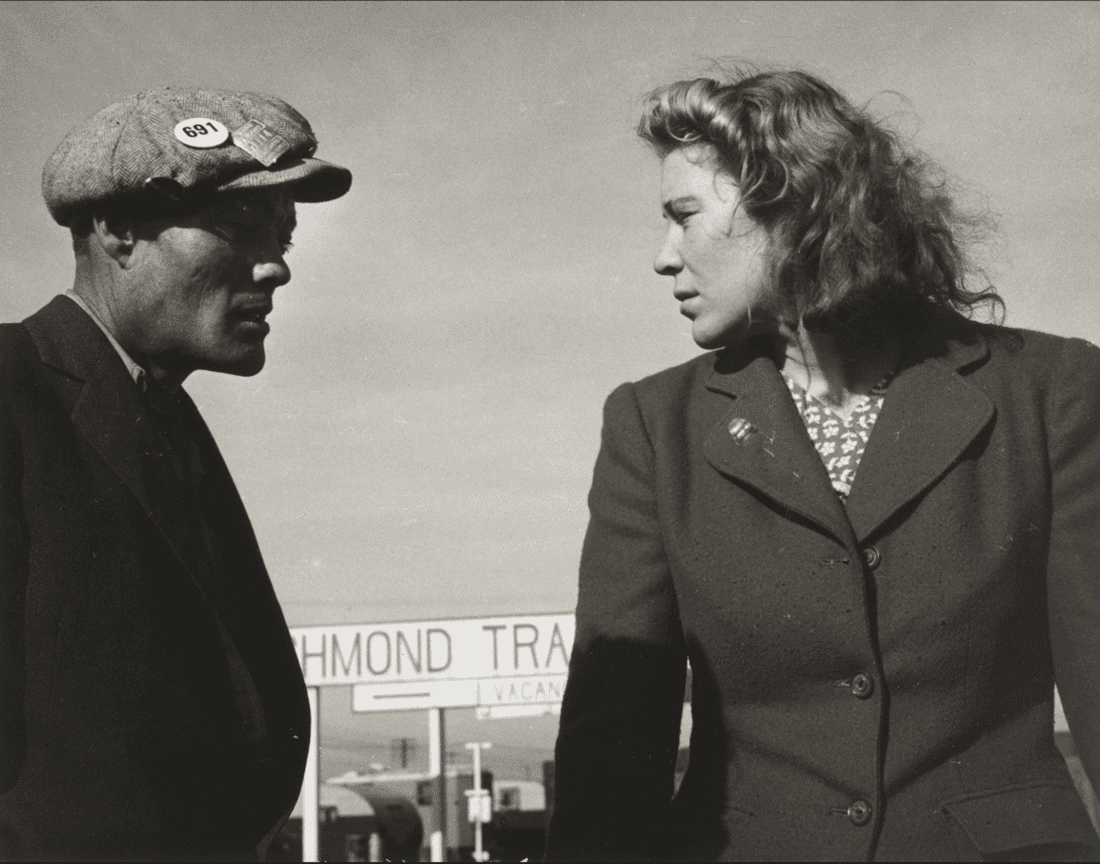

Argument in Trailer Court, 1944.

Lange was often quite deliberate in her compositions, one theme in her work expressed here by the woman being well-lit and visually dominant in the picture, while the man is dark and shadowy.

Gordon Parks (1912 – 2006)

Starting his photographic career working for the FSA and the Office of War Information, Gordon Parks became one of the most influential photojournalists of his time, remarkably photographing the human condition of marginalized Americans in the 1940’s and beyond. Affected by the earlier FSA photographs of Dorothea Lange and others, Parks bought a camera and taught himself how to use it.

“I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs. I knew at that point I had to have a camera.”

A versatile talent, Parks was also a distinguished musician, author, and filmmaker. As a staff photographer at Life magazine, Parks demonstrated his versatility with fashion photography and with portraiture of important figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr., Marilyn Monroe, Louis Armstrong, Leonard Bernstein, and Muhammad Ali.

American Gothic, Washington DC, 1942.

This photo is among his first, part of a series on Ella Watson, a government cleaning lady, that is so quietly powerful and evocative of the Grant Woods painting that it became his most well-known.

Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956. Making a potent social commentary in a single image, the beautiful elegance of the woman and her niece waiting in front of a movie theater contrasts with the garishly grim neon sign above them. Joann Thornton Wilson, the woman, later wondered why Parks did not have her fix the one flaw in her clothing: the fallen slip strap. Parks was meticulous about details in his photos, so it may well have been to make her more human, to make it clear this was not one of his fashion photos.

Carl Finkbeiner

Mobile: 610-551-3349 website instagram facebook linkedin digitalphotoacademy